Combat and rain

Nai-Ni Chen at John Hancock Hall

By MARCIA B. SIEGEL

The Phoenix

May 13, 2008 11:58:40 AM

Taiwanese choreographer Nai-Ni Chen danced with Cloud Gate Dance Theater before moving to New York in 1982, and her work, like theirs, is a suave amalgam of traditional Chinese elements and modern dance. Chen’s company of 10 dancers appeared Saturday night at John Hancock Hall, sponsored by the Foundation for Chinese Performing Arts. The program demonstrated how the traditions can nourish contemporary dance, with practical tools like movement and symbolic objects as well as philosophical and literary themes.

Chen’s movement style was showcased in the opening piece, Raindrops, for four women. Wearing pastel silk halter-top jumpsuits with flying panels of silk front and back, the women clustered together at first, revolving and lifting their arms with palms upraised. They skimmed across the floor in tiny sidesteps and tilted swirls, their torsos undulating in elegant zigzags and curves. With small sudden jumps or abrupt tumbles to the ground, they’d interrupt their swift trajectories, then recover.

The music, by three composers (Henry Wolff, Robert Rich, and Sainkho Namtchylak), changed from high, resonant bells to deep gamelan gongs to rhythmic drumming with Jew’s harp and electronics. After the meditative beginning, the women danced with rice-paper umbrellas, possibly celebrating the rain they’d been praying for. Then they returned to their quick running and jumping patterns for a lively celebration.

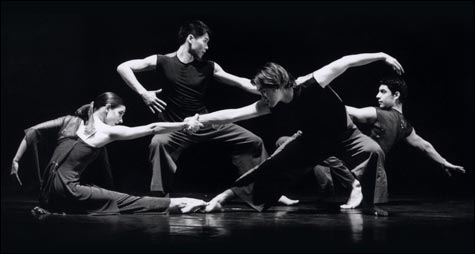

Following Chinese dance conventions, Chen’s men and women almost always dance separately, or at least in separate styles. But though the women looked decorative and moved in small spheres most of the time, they never looked cute or doll-like to me. In fact, with the incorporation of martial-arts skills, they could oppose the men in contests of attack and evasion — a duet or a duel with fans in The Way of Five — No. 2, an escalating group counterpoint of dominance, submission, and recuperation in Unfolding.

To show the classical roots of these encounters, Chen included a dance for an acrobatic warrior from China’s Kunqu opera, as adapted and performed by Yao-Zhong Zhang. A former actor with the Shanghai Kuan Opera troupe, Zhang stomped on his platform shoes, stroked the long feathers streaming out of his headdress, and twirled two spear-like batons while doing helicopter turns.

In Chinese opera, you overcome your opponent with athletic prowess and intimidate him by means of resplendent costumes, headgear, and make-up rather than brute force. Weapons evolved into fans, to deceive and surprise. Similarly, long sleeves attached to a robe could conceal and, when flung out around the character’s body, dazzle and distract. Nai-Ni Chen described gorgeous white halos and ripples around herself in Passage to the Silk River. But she wasn’t only manipulating the sleeves, she was dancing herself, in clever chaîné turns and flourishes that animated the silk.

Six women carried eight-foot-long rods in Bamboo Prayer, making the flexible props into extensions of their bodies. Held vertical as the dancers ran in circles, the sticks swayed like saplings. Thrust along the floor or placed in certain patterns, they could link the dancers, provide grids for stepping games, or perhaps even invoke magic spells.

Chen’s program notes told us about the legends and metaphysical images that underlay all these dances. Lindsey Parker represented the spirit of the river and Qiao Zeng the fisherman getting his sustenance from her spring floods. But watching the dance, I thought they could have been lovers or even lifelong companions on a fateful journey, as he poled an invisible boat and she hovered around him.

For the finale, Festival, the whole company joined in a procession of dancing, tumbling, flag dances and a calligraphic extravaganza of long silk scarves in bright colors, foaming and spurting above the stage.

No comments:

Post a Comment